Homelabs I: tsnet feels like cheating

Posted on: 2025-12-26I: Context

I have been using the Asus TUF FX505GT since early 2020, and it got me through college, from coding to games and everything in between, so when I got myself a new PC, I knew I couldn’t just sunset the laptop this easily; Partly for sentimental reasons, partly because I don’t actually have a spare machine lying around yet (what if I travel?)

Anyways, I pulled out its larger SSD for my PC, dropped in a brand new smaller one, installed Ubuntu, and boom, server! just a playground though. We gotta do something with it.

There are honestly a lot of directions you can take a device of this nature now, and there are virtually no limits whatsoever, after all, the i5-9300H paired with 16GB RAM sounds fairly powerful for small use cases right? perhaps:

- a database? (why)

- or a media server? (reasonable)

- a minecraft server? (every cs student’s canon event)

- a build agent?

- a safe testing playground?

In practice though, there is one limit that shows up immediately - how do you reach it, incase you want to operate outside your home? Having god like hardware doesn’t matter here if you can’t reach it right?

Why does this happen?

CGNAT, in most cases or otherwise known as Carrier-Grade Network Address Translation.

I’m not an expert in all of this by any chance but, traditionally, your home router gets a public IP address, and everything inside your network sits behind it. With some port forwarding and firewall rules, you can expose a service to the internet. with CGNAT however:

- the ISP does not give you a public IPv4 address

- instead, you share one with hundreds or thousands of other users

- the router itself is behind another NAT, owned by the ISP

I’m not really sure exactly why they use CGNAT but surely it couldnt be just a way to conserve IPV4 address, because if we all suddenly started using IPv6, I still don’t see ISPs giving a static IP for free. perhaps there is security risk among the list of reasons but oh well. who knows.

What did I chose?

Well I do have a golang backend running on GCP serving my other site. it runs fine, and by design, it talks to 3-4 external APIs to help populate my site.

Wouldn’t it be nice if I could track latencies? but surely, a database isnt needed for this, heck I could just fmt.Logf(""), read the logs on Cloud Run console and call it day. But no, I really wanted to get my hands on PostgreSQL and NOT use any managed services for the same.

Well I just found my use case: a database server (sigh), and so began my research. I’m in no way stranger to databases, linux or even networking in general, but I really wanted a way for GCP to talk to my machine without too much effort. (Although it would have been a very nice learning experience)

II: VPNs and Tailscale

How VPNs might help here

Well thoughts can start from:

“maybe VPNs could help”

to:

“How do I set up one, so that it runs on a server at my home without my interaction at all but is secure as well? Although tempting, it seems too much work”

and finally land at:

“Isnt Cloud run a severless service with no easy exposure to the filesystem and hardware devices like NICs? how will I configure the VPN in cloud run?”

For homelabs, a remote-access VPN (or a peer-to-peer mesh VPN) is often the simplest, safest way to let cloud services or mobile devices reach private infrastructure without punching holes in your router - but this falls apart in situations like this, until you stumble across tailscale. an absolute gamesaver here.

About tailscale

While researching on places like r/HomeNetworking and r/selfhosted and even Gemini, I frequently saw mentions of “tailscale” by humans and bots, and how great it is. Naturally I got curious. Went to the website and was sold. It at least deserved a go. Installation wise, its dead simple, just follow the guide here. In a nutshell though, its just

curl -fsSL https://tailscale.com/install.sh | shfollowed by

sudo tailscale upThats it. follow the on screen prompts and you’re set. Cool, a VPN, I thought. All of this was nice and easy for personal access but now what? This doesnt solve the serverless problem?

Turns out it actually does.

userspace networking

I for some reason subconsciously assumed that networking is an OS thing - never gave it a second thought: Packets come in through a NIC, the kernel handles TCP/IP, sockets get exposed to applications, and that’s that. If you want to do “real” networking, you need access to the machine, the interfaces, and usually some level of privilege.

But thing is, TCP/IP doesn’t actually have to live in the kernel. Thats the idea of userspace networking. This works because, think about it, TCP/IP is just logic. It’s traditionally implemented in the kernel for performance and shared access. That means if you’re willing to pay a small overhead, you can implement the entire networking stack in userspace, inside your application process, decoupling you from the OS when it comes to networks.

tsnet

tsnet is a goated go library maintained by Tailscale that uses the idea above and hence lets you embed an entire Tailscale node inside your Go binary.

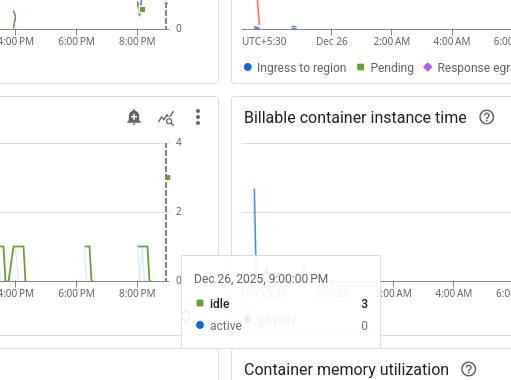

Once the binary starts, it authenticates with Tailscale, joins the tailnet, gets its own identity, and suddenly shows up in the admin console like any other device. Except this “device” happens to be a Cloud Run instance that didn’t exist a few seconds ago. It’s very neat.

Make the authentication credentials as Ephermal, and once the cloud service winds down, the device will get auto removed after a while, for small, hobby projects, this setup helps keep the limits in check.

We will use this.

III: Bringing Everything Together

We can start actually doing stuff now.

the database server

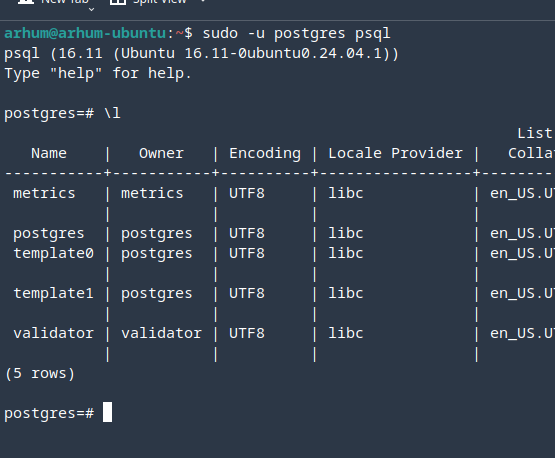

This blog is NOT a full follow-along tutorial, and configuring postgres is as standard as it gets. just follow this and call it a day. The neat part is how we reach this, rather than the database itself. Since we didnt install Ubuntu server on it, you can also go ahead and install pgAdmin

After installing it can, not should look like:

A possible approach to utilise tsnet

Before writing any code, I had a few non-negotiable requirements:

-

The database is optional: The app should continue to function even if the database is unavailable. Sometimes the laptop is off. That’s fine.

-

Logging must be asynchronous: Writing metrics to the database should never block request handling.

-

Startup must not be blocked by the database: Cold starts on Cloud Run are painful enough already. The app should come up immediately, regardless of database state.

-

Failure is acceptable: If database writes fail, the world does not end. At worst, some logs are lost. Those can be handled later — maybe via log parsing, maybe via a message queue in the future.

The shape of the code becomes much more obvious once you accept these constraints, we will quickly go through each parts.

a. Making the Database Optional

Instead of returning a *sql.DB directly, I wrap it in a small struct with a mutex and allow it to be set later:

type DBConnection struct {

db *sql.DB

mu sync.RWMutex

}

func (h *DBConnection) SetDB(database *sql.DB) {

h.mu.Lock()

defer h.mu.Unlock()

h.db = database

}

func (h *DBConnection) GetDB() *sql.DB {

h.mu.RLock()

defer h.mu.RUnlock()

return h.db

}This lets the rest of the application ask, “Is there a database right now?” without assuming the answer is always yes.

If it’s nil, we simply don’t write to it.

b. Non-Blocking Startup

func InitDb(cfg *Config) *DBConnection {

conn := &DBConnection{}

if cfg.Database.Host == "" {

log.Println("[INIT] skipping database..")

return conn

}

go func() {

// database initialization lives here

}()

return conn

}From Cloud Run’s perspective, the service starts instantly. Whether the database connects in 2 seconds, 20 seconds, or never at all is irrelevant to request handling.

c. Calling Tailscale Only When Needed

Instead of hard-coding tsnet, the decision to use it is driven entirely by configuration:

if cfg.TailscaleAuthKey != "" {

log.Printf("[INIT] need tsnet for host: %s\n", cfg.Database.Host)

// tsnet setup lives here

}d. Custom Dialer

Instead of asking Postgres to connect using the OS network stack, I override the dialer and route connections through the embedded Tailscale node:

pgxConfig.DialFunc = func(ctx context.Context, network, addr string) (net.Conn, error) {

return s.Dial(ctx, network, addr)

}At this point its a normal outbound connection from the service, which is essentially modified by tsnet to look like one. in reality, we are connected to the tail-net, which means we can reach our database.

e. Back-off strategy

Instead of crashing or blocking forever, I use a simple backoff loop:

for {

err := db.PingContext(ctx)

if err == nil {

conn.SetDB(db)

return

}

time.Sleep(backoff)

}This is not robust though, just enough. I will be honest, we can engineer it better, but for now, we move on.

seeing it in action

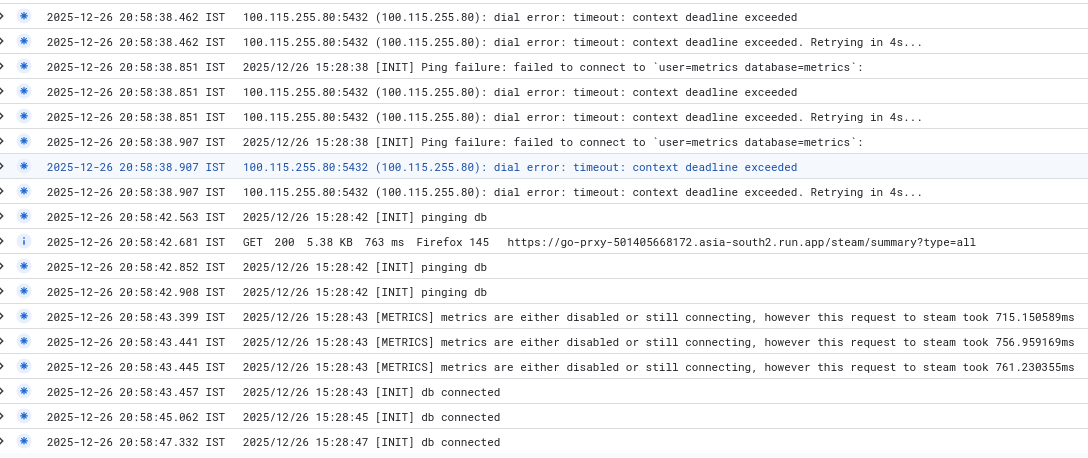

As you can see it finally connected after a bit of work (ALL outbound are billed, so this isnt ideal actually), the reason you see 3x the logs is because Cloud Run spun up 3 instances probably because i reloaded very fast:

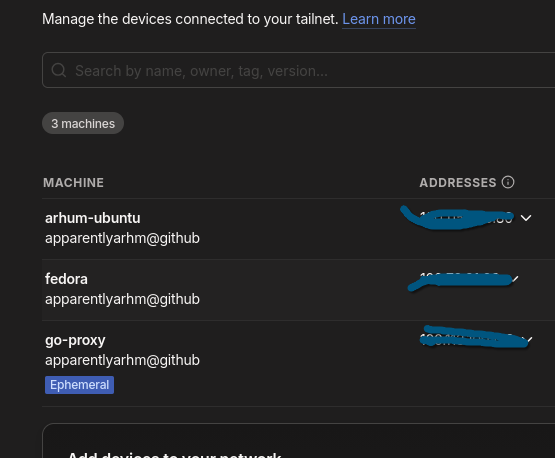

moreover, while it set itself up in the tailnet, the app also showed up in the console as a device:

refactoring the code to support logging

Originally, I wrote all external APIs in the form of a Service, with a client struct associated with it. Consider this for an example:

type Client struct {

config config.GitHubConfig <- has secrets/vars/tokens

http *http.Client

}this struct can have methods attached to it that contains the business logic of fetching, transforming, if necessary.

since we inject a http client to every service, we can create a custom http.Client with custom logic on top of making the requests, that means, I can write a logging logic there, which uses the database, without touching individual call sites.

Go already gives you the perfect hook for this -> http.RoundTripper.

we can define:

type MetricTransport struct {

Base http.RoundTripper

DB *config.DBConnection

Service string

}then,

func (t *MetricTransport) RoundTrip(req *http.Request) (*http.Response, error) {

start := time.Now()

db := t.DB.GetDB() // we either have it or we don't

// Default to the standard transport if none is provided

base := t.Base

if base == nil {

base = http.DefaultTransport

}

resp, err := base.RoundTrip(req)

duration := time.Since(start)

// If there's no database, we stop here

if db == nil {

log.Printf(

"[METRICS] metrics disabled or still connecting :: %s took %v",

t.Service,

duration,

)

return resp, err

}the actual DB write can occur in a goroutine. A few important things to note here:

- If this goroutine never runs, nothing breaks

- If the database disappears mid-request, nothing breaks

- If inserts fail, nothing breaks

go func() {

statusCode := 0

if resp != nil {

statusCode = resp.StatusCode

}

db.Exec() // your insert code here, standard.

if dbErr != nil {

log.Printf("[METRICS] DB Log Error: %v\n", dbErr)

}

}()Now that we have a setup, we can have something like:

githubHttp := &http.Client{

Timeout: 10 * time.Second,

Transport: &telemetry.MetricTransport{

DB: db,

Service: "github",

Base: http.DefaultTransport,

},

}The GitHub client itself has no idea that metrics exist. Repeat this for every service.

What I like about this approach

notice that it didn’t require:

- rewriting existing services

- adding logging calls everywhere

- passing context objects through half the codebase

- Metrics became an infrastructure concern, not a business-logic concern.

Which is exactly what I wanted.

IV: Closing thoughts

With that, we have successfully self hosted a database, along with good programming patterns throughout a golang application. Thoughts-wise I have nothing to say except that self hosting is fun, even if there is no real use case or you break best practices sometimes here and there.

Hopefully it was an insightful read for you!

A small disclaimer: if you are reading this, and want to comment on anything, you'd have to reach out directly. this platform is still in its infancy and im yet to add all the "social" features; I also highly doubt my content would be engaging enough anyway to spark engagement but you never know when people want to discuss something, or, .... hate lol